Paths And Trails

Women’s Architecture

Throughout the ages, women have contributed to the structure of public buildings. Indeed, Queen Helena was one of the most important among them, followed by QueenEudocia. The phenomenon was renewed during the Mamluk era, with women building numerous educational and social institutions. Indeed, one cannot overlook Khaski Sultan and her Tikiyyah (free kitchen).

Trail’s Nature and Stations

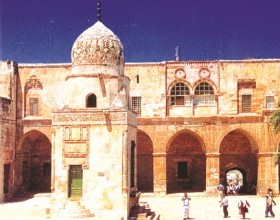

This trail is located in the heart of the Old City. It is divided into two parts. The first part includes ‘Aqabat al-Takiyya and the Bab al-SilsilaStreet,and the second extends to the inside of al-Aqsa Mosque at its western wall. This trail is relatively short and easy, and like the other trails, it could be visited with all its stations or divided into parts. This trail is limited, because it presents in its majority the façades of buildings, since it is difficult to enter most of the buildings included in it. Some of the trail’s stations cannot accommodate a high number of visitors. The trail needs between 1.5 and 2.5 hours to complete.

The trail’s stations are:

1- Qasr al-Sitt Tunshuq l-Muzaffariyya

2- Turbat al-Sitt Tunshuq

3- Al-’Amira al-’Imara (Khassaki Sultan)

4- Turbat Turkan Khatun

5- Al-Madrasa al-’Uthmaniyya

6- Al-Madrasa al-Khatuniyya

7- Al-Madrasah al-Ghadiriyya

8- Al-Ribat al-Mardini

Introduction

Women’s Contribution to Charity

Islam equated between men and women in the area of religious and basic duties related to charity and doing good. Although Arab Islamic society was primarily patriarchal, some women had a clear role in many facets of life, particularly those who were close to the ruling authority, such as princesses, sultan’s wives, or mothers or wives of rulers or influential people. These positions paved the way for them to undertake acts of welfare and charity, especially when financial, administrative and social resources and capabilities were available. Given Jerusalem’s position and importance in Arab history in general and Islam in particular, several charitable and wealthy women were attracted to it and contructed buildings and structures there.

Jerusalem as the Incubator of Women’s Heritage

In following the architectural and social activities in the city of Jerusalem over the Islamic eras, one realizes that feministic heritage found its way into the city and among its residents early on. Though it does not parallel or competes with the heritage of men in the Old City, it is nevertheless noticeable and indicative of major diversity and giving. This is because the majority of architectural activity was done by men in power, whilst that of women was done by those who belonged to ruling or wealthy families.

The heritage of women, or al-Khawatin as some like to call them, started early in Jerusalem. The beginnings date back to the Abbasid era, when the mother of al-Muqtadir Billah renovated the doors of the Dome of the Rock. The Mamluk era, with its characterized stability and calm, saw clear activity by women, represented by the establishment of public and private buildings and structures. The largest house or palace representing civil architecture in Jerusalem is attributed to a woman, al-Sitt Tunshuqal-Muzaffariyya. Also, the largest and greatest social charity organization from the Ottoman era, known as the al- ‘Amira ‘Imara , is attributed to the wife of Ottoman Sultan Suleiman l-Qanuni (Suleiman I or Suleiman the Magnificent). She was famously known as Khassaki Sultan and her building structure is considered one of the greatest organizations, not only in Jerusalem, but also in Palestine and the Levant.

The Diversity of Women’s Heritage

Women’s heritage in Jerusalem is diverse, ranging from the small copper bowl to grand architectural projects involving 50 employees with allocated funds from nearly 50 towns and villages. The activities included acts of compassion towards Sufis and the poor, providing HolyQurans to the faithful, and constructing buildings for charitable pursposes.